Ambiguity and Multi-layeredness

Over the last couple of decades the tremendous increase in the sheer availability of historic recordings has been truly remarkable. So much more material than ever before has become readily available to the general public. For example, Rachmaninoff’s recording of the Chopin Nocturne Op. 9 No. 2, has attracted nearly 1,5 million listeners in the three years since it was first posted on YouTube. This is a truly amazing figure, that would have seemed absolutely incredible even a few years ago. It seems that many of the old recordings attract a massive number of listeners, often far beyond the Youtube demand for contemporary classical stars playing the same music.

![]()

This is great news for those of us who are deeply in love with the playing style of this period and feel we have much to learn from it. At the same time it is somewhat surprising to observe that this overwhelming interest does not feed back into modern performances to any great extent. This is all the more more surprising given the great interest in historically informed performance practice.

There is no question that there are historically informed performers that have taken on board some significant elements of the performance styles of the early twentieth century. Still, if we look just at pianists as an example (but the same can equally be said of orchestras and conductors), we see no performers even in the remote proximity of Edvard Grieg, Alfred Grünfeld or even the somewhat later, legendary, Alfred Cortot.

There is of course, no one simple explanation for this situation. The playing styles of the early recording history are certainly very varied. It is also true to say that some elements of the performance styles are shockingly different from modern ways of playing, even when considering modern authentic performances. Others, on the other hand, are more comfortable to the modern ear and are soon welcomed in. But one must remember, whether we like it or not, that we are here presented with the real thing – real performance history – not performance history the way we would like it to be, nor the way we have read about it. The early recordings, says Roger Philips in ‘Early Recordings and Musical Style’, “…present us with the whole truth, not just what we want to know.”

Many researchers and writers have dealt with our recording history – even as far back as in the first decades of recording history. Already in the nineteen twenties, the composer and principal of the Royal Academy in London, John Mc Ewen was researching into rubato as it was actually played, rather than how it was talked and written about He looked at performances of a number of great pianists, using piano roll recordings with the timings already punched out on the paper roll. More recently, the interest in recording history among academic researchers has flourished and a number of performance issues have been addressed from the perspective of a modern listener. This is cutting edge music research and is growing apace. We are clearly not alone.

If all this is so, if there is a real and developing interest in this old stuff, why don´t we see these performance styles feeding more back into to modern performances, the way one would expect? Where is the rush that we saw with the baroque and classical periods? Early music research and performance has changed the way we all play and listen to that music even if we are not on the team as it were.

Perhaps part of the reason is that many elements of the style seem alien to us on first acquaintance. It is also because we are confronted, for the very first time, with a history that is truly aural and as such to a much greater extent complete. Being complete, it often contradicts both what the performers and composers themselves seem to have said in words and in the musical notation; and perhaps more significantly, contradicts many of our strongly held modern musical values and beliefs.

Can we summarise what these values include? Here are a few that I think we can all recognise: A very literal approach to the score and its apparent demands, an overriding attention to orderliness, togetherness, clarity and rhythmic steadiness. Features like the rushing towards a point of emphasis, the lightened of short notes, non-synchronized hands or chords in keyboard playing, and the much greater level of tempo modification and rhythmic variation often indicate to a modern listener a lack of control and disorderliness. These indeed are regarded as grave sins in the twenty first century.

All of the elements mentioned above are dealt with in various written sources. In the articles on this web we will among other things discuss these matters from the perspective of Grieg´s performances, and relate them to other performers of his time. There are even some issues perhaps not dealt with in a fully comprehensive way that we would like to visit, elements we have found in the performances of Grieg and similarly in many of his contemporaries´ performances.

AMBIGUITY and MULTI-LAYEREDNESS

Among the most powerful features of performances of Grieg and his contemporaries, is the frequently appearing presence of two or more directional tendencies, acting simultaneously. We think this multi-layered phrase trajectory is of tremendous importance and a very exciting component of the style. It is found so often in the greatest performances of the time, where it plays an essential role. It is probably an area where the old and the new are furthest apart.

Among the most powerful features of performances of Grieg and his contemporaries, is the frequently appearing presence of two or more directional tendencies, acting simultaneously. We think this multi-layered phrase trajectory is of tremendous importance and a very exciting component of the style. It is found so often in the greatest performances of the time, where it plays an essential role. It is probably an area where the old and the new are furthest apart.

In the very best performances, these multidimensional tendencies create a deeply imbedded ambiguity. But this ambiguity is almost always subordinate to a a firm, non ambiguous, overall line. This certainly is a very strong characteristic of Grieg´s personal performance style. It quite often appears as a result of an interaction between ‘hard’ composed and more fluid performer added elements. These elements affect the contour of the musical phrases, the longer sections, and the way the phrases and sections link together.

It was common practice at the time for performers to disregard the apparently clear sectional forms found in the written score, and to constantly shape phrases independently of it. This is not to say that this is in any way counter to the intention of the composers, in fact quite the contrary. After hearing composers perform themselves, this seems to be an obvious way of shaping most of the musical material. The emerging ‘counterpoint’, is also evidence of the a great limitation in our notational system. This kind of counterpoint involves a constant dialogue between solid forms as they are found in the score on the one hand and very fluid constantly evolving shapes, on the other that are performer induced. As the score has become more sacrosanct these solid forms have often assumed preeminence at the expense of a much richer internal dialogue.

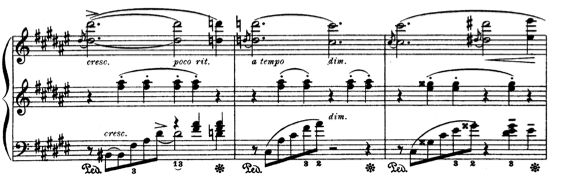

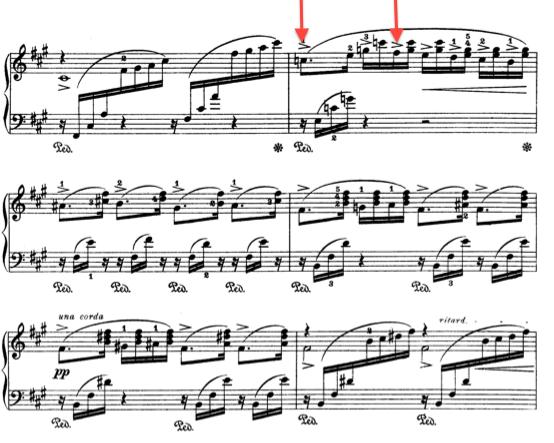

This also proves the incredible significance of a living performance tradition. Listen to Rachmaninoff playing the middle section of his Prelude in c# minor in a recording from 1928, a great performance of this much recorded piece:.

This also proves the incredible significance of a living performance tradition. Listen to Rachmaninoff playing the middle section of his Prelude in c# minor in a recording from 1928, a great performance of this much recorded piece:.

Many things are happening here, lets look at a very few: Rachmaninoff´s wonderful shaping of this phrase is nothing like the apparent phrase structure in the score. Central is the gravitational weight of the slow introduction that exerts its power all through the example above. The Agitato beginning is no solid start of a new section but elided with the slow opening bars of the piece. The Agitato seems to ‘fall forward ‘ during its first two bars and the join between bar four and five becomes consequently not a simple a tempo at the point of the repeated theme but a point of release emerging slowly. What we hear at just that point (within the box) is the preparation and approach of a phrase ending, which is overlayed by a strong impulse to the repeated phrase, a two-layer phenomenon with the contour of the performed phrase in counterpoint with the notated structure. There is an ambiguity occuring in the presence of overlapping functions, in this example: a “beginning-end” ambiguity.

The middle of bar 4 takes us back to the slow introduction as the forward motion burns off, but by a wonderfully characteristic slight of hand Rachmaninoff makes the third beat both the arrival and the point of new departure. We already move within the 4th beat towards the release of tempo felt at the start of the next bar, bar 5. The barline has a presence here, and not just a theoretical one, but is countered by the fluid shape that makes the apparent inactive 4th beat a central part of the action.

The words make this seem very ungainly but take the time to play the example more than a few times. Its wonderfully creative playing full of musical density beguiles the ear.

In Grieg´s performances there is rich evidence of similar overlapping phrases. In the following example, To Spring, we hear a related strategy:

In a similar way to Rachmaninoff, Grieg is eliding the two sections – the one ending in the first bar of the marked section, the other beginning with the second bar. In his performance, the impulse to the entry of the Coda is overlaying the end of the preceeding melodic line. In this way, Grieg creates an ambiguity which – along with the sophisticated rubato – works against the rather schematic outline of this lovely little piece. He masks the seams of the piece, and creates a new dynamic outline, of which there is no trace in the score.

As an example of a more modern approach to the same transition we have included the music example below. There is no question that the differences in tempo here and in upcoming reference recordings are of great importance. This example still highlights the fundamentally different approach to the transition, which is our point here.

![]()

There will always be a question as to the aesthetic value of ambiguity. In ‘the Practice of Performance’ (ed. John Rink), Janet Levy suggests that “much music theory and analysis has concerned itself with attempts to ‘disambiguate’ ambiguous meanings of musical events and passages in which one or more alternative interpretations appear possible.” Levy further suggests that this is especially true in harmonic analysis, but in our view, her observation is highly relevant even in the context of performing.

There is a strong tendency now among performers to reinforce formal shapes rather than encourage contradictions, to clarify rather than to mystify. A phrase ending for example, will often be dynamically reduced to match a descending melodic shape, perhaps with a slight rhythmic softening and phrasing off, perhaps also a slight easing of the general tempo. All these small events delineate the structure and add to stability and clarity, but are most probably counter to the intentions of most composers in the romantic period who expected greater complexity and internal conflict in the finest presentations of their works. When all tendencies within a transition or a phrase ending actually do point in the same direction, it is usually introduced as a striking effect.

TRANSITIONARY STRATEGIES

In his ‘Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music’ Ferrucio Busoni wrote: “Indeed, all composers have drawn nearest the true nature of music in preparatory and intermediary passages, …. where they felt at liberty to disregard symmetrical proportions and unconciously drew free breath.”

In Busoni´s own recording of Chopin Nocturne F sharp major opus 15 no. 2 – perhaps one of the most remarkable piano recordings ever – he confirms the significance of the quote above even with regards to performing. In the transition to the middle section of the Nocturne, Busoni demonstrates a fundamental understanding of directional ambiguity and the eliding of lines, and creates a moment of musical “truth” imprinted in our minds forever.

In his performance, Busoni manages to create a moment of weightlessness in the transition which is not merely a matter of broadening the line or holding back the tempo. Only trough a tremendous control over the finest rhythmic details, Busoni is able to give the transition this impression of directional ambiguity. The result is a magic feeling of the middle section not beginning, but emerging from the transition.

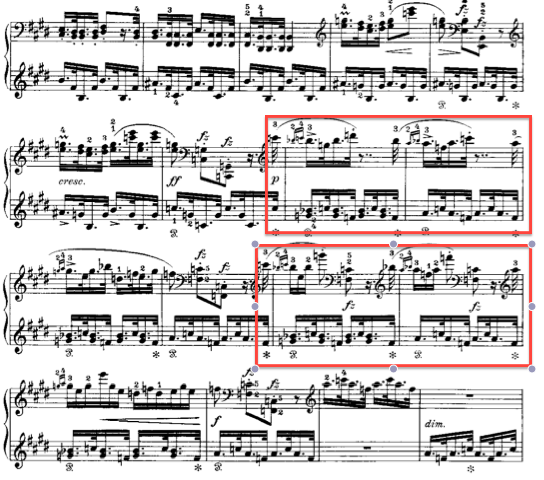

Though perhaps not emerging in quite the same, striking way as the middle section above, the second theme of the Finale of Grieg´s piano sonata is introduced in a very typical manner of his. The word “emerging” probably describes the appearance of this theme as well – emerging as opposed to a clear cut beginning.

Even in a transition like the following, which in some way feels like a full closure – and is indeed always performed as one – we find in Grieg´s performance a clear overlapping of the sections with a sudden lift to a new tempo region (not indicated in the score). The very slight ritardando is not followed through to the new section, but interrupted by an impulse to the new section which clearly anticipates the projected or expected beat (Notice also how Grieg changes register from his own notation, and gives us a more ‘orchestral’ version in his performance):

Generally speaking, Grieg almost always performs the end of a phrase or section with a direction pointing into the following section. Closed endings within the pieces are in fact very rare. The joins are fewer, the formal sections appear to be longer and the structure consequently appears to be of larger scale. This is part of the reason why his performance of for example To Spring has such incredible unity – it appears to be one continuos, unbroken line

In Grieg´s performances, we see the constant avoiding of any obvious combination of strategies at phrase endings or transitions. A combination of for example relaxation, diminution, and retardation with a clear cut, prepared turning point of the phrase is virtually non-existant in his performances. Listen to the following transition from Grieg´s own performance of the Piano Sonata op. 7, 3. mvt:

Below is similar example to illustrate a typical modern performance approach to these transitions:

To most of us, the last example represents a very familiar way of shaping the material. But it is certainly not representative of Grieg´s own performance style. It represents a more modern approach to interpretation.

![]()

It is important to make the distinction between ambiguity, and uncertainty or vagueness. These are not interchangeable, but rather opposed terms – ambiguity requiring identifiable possibilities. However, uncertainty of direction or even vagueness is also to be found, very exceptionally, in Grieg´s own performances. This effect can be heard in the linear ritardando into the recapitulation of Butterfly, where the unclear turning point of the direction gives a strikingly vague effect.

In my own performance of the first movement of the Piano Sonata (in the transition to the recapitulation), I have in fact chosen a somewhat similar strategy to Grieg´s Butterfly. Although of a different format, we believe the gradual introduction of the “a tempo” of the recapitulation fits this movement as well as Butterfly. It serves the purpose of loosening the firm structure slightly, and gives a feeling of expanding the otherwise short development section a little bit into the recapitulation, overlaying those formal sections of the movement.

COMPOSED AND PERFORMED AMBIGUITY

Depending on the composer and the style, the written score will to a varying degree be inflected by composed ambiguity. On paper, the music Grieg recorded is perhaps not so rich in composed ambiguity, Schumann´s music on the other end of the scale is saturated with it. Looking at for example Kreisleriana, 1 mvt, we see a composed ambiguity as a result of a three layer metrical conflict. In performance, the dynamic force and interaction between the metrical levels is fundamental to the characterisation of this piece, more than the emphasising of one dominant pulse.

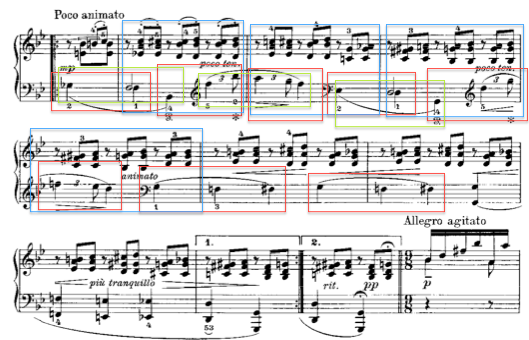

In Ballade we find a somewhat related example in variation number 7:

Metrical ambiguity

When discussing ambiguous tendencies in music, we often consider how this ambiguity is perceived by or communicated to an experienced listener. Without question, the perception of the ambiguous tendencies is to some extent culturally conditioned – we are for example often dealing with a conceptual ambiguity emerging from an interaction between written and performed elements. Recognizing this ambiguity often requires a thorough knowledge of the score. An example of this is the ambiguity emerging from some kinds of metrical conflict, specifically the conflict between the notated meter and audible metrical structures created by accentuations of all kinds. A famous example of this is the second theme of the last movement of Schumann´s Piano concerto.

In Grieg´s music, there are a number of places where a similar ambiguity is embedded in the score itself, such as in the second theme of the first mvt of the Sonata. The red arrows indicate the normal point of gravity in the bar, the purple indicate the accents disturbing the regular divisions:

We find another, strongly ambiguous section towards the end of Ballade, where the metric divisions, accentuations, and dynamic indications all pull in different directions, creation a whirling chaos at the climax of this large scale piece. The blue boxes indicate the normal metric division, the red lines indicate metric impulses that disturb this pattern; one result being the emerging purple division:

Although we do find a great number of brilliant examples of composed ambiguity in Grieg´s music, most certainly in his Peasant Dances Op. 72, even more interesting in our context is still to observe how Grieg introduces ambiguity in his performances, particularly the kind of which there is no indication in the score. Grieg´s performances are very rich in performer introduced ambiguity, the striking examples being Bridal Procession, Butterfly, and To Spring. A really remarkable example is taken from Bridal Procession, where Grieg in a steady 2/4 measure suddenly removes a crotchet from several subsequent bars, of which there is no indication at all in the score:

Listen also to how Grieg performs the line of the following section of Butterfly in relation to the written structure, and observe the conflict between the metric organization and melodic structure of the performance. The accentuation, and the way he springs off the third semiquaver of the second beat gives the phrase a clearly different contour than the apparent phrasing and metric organization in the score:

The core of the development section in the first movement of the Piano Sonata is a sequence, introducing composed metrical ambiguity. In performance a strong directional ambiguity is needed to avoid the sectionalizing of this very brief development section:

Agreeing that ambiguity requires the presence of at least two identifiable possibilities, ambiguity to one listener might very well be perceived as vagueness and uncertainty to another listener with a different stylistic reference. This certainly becomes a problem when listening to Grieg´s recordings for the first time, and was precisely the problem we both had when first listening to Butterfly. In fact, this culturally conditioned ambiguity very often emerges in the twilight zone between the performed and notated meter, such as the music example above (Butterfly).

Directional ambiguity

Although the perception of metrical ambiguity to some extent is culturally conditioned, the perception of directional ambiguity certainly isn´t. The directional ambiguity mentioned above in To Spring ( is it the beginning or the end of the phrase, or both?) and the kind we hear in Rachmaninoff´s C-sharp minor Prelude, we believe are more generally recognizable, adding an almost physical and ‘sculptural’ dimension to the music. This sculptural dimension is in our view characteristic of the greatest performances of the period, in fact of any period. We often hear continuous sub-currents created by opposing tendencies in the material. There are multiple directional layers which constantly work against the division of a work into smaller sections, and help create larger dynamic shapes.

In listening to Alfred Grünfeld (picture) and Carl Friedberg, we hear a demonstration of this. Grünfeld and Friedberg were both friends of Brahms; Grünfeld was the court pianist in Austria-Hungary, the younger Friedberg was one of Clara Schumann´s most important students, and played to Brahms. These are truly wonderful performances, and it is my hope that you will take the time to listen several times, and discover the tremendous quality of this playing.

In listening to Alfred Grünfeld (picture) and Carl Friedberg, we hear a demonstration of this. Grünfeld and Friedberg were both friends of Brahms; Grünfeld was the court pianist in Austria-Hungary, the younger Friedberg was one of Clara Schumann´s most important students, and played to Brahms. These are truly wonderful performances, and it is my hope that you will take the time to listen several times, and discover the tremendous quality of this playing.

Alfred Grünfeld, Brahms´ Capriccio op 76:

Carl Friedberg in Brahms Op 118

The distinguishing between, or separation of more or less important material through subtle tempo changes, is a very central characteristic of the period. The best performers demonstrate how the most exquisite level of shaping relies on the sense of multiple directional tendencies at work – the simultaneous interaction between material with different directional orientations. In Grieg´s case one could say this is integrated in his performance to such a degree that it even suggests a personal style – this is probably what Grainger had in mind when describing the ‘feverish’ character of Grieg´s playing.

Grieg´s pulse and tempo are constantly affected by minute changes of direction, creating complex undercurrents and opposing tendencies in structures that are often visually simple. Even though this ‘feverish’ character is indeed a strong personal characteristic of Grieg´s playing, the undercurrents and abundance of opposing tendencies in the performances are far more important when looked upon as a stylistic feature in a large group of the performers of the time.

If we listen to To Spring, we hear a continuous change of direction in the phrasing, which certainly isn´t whimsical playing, but can be described as two opposing directional layers.

Following the recreations, we have recorded Grieg´s complete Piano Sonata and Ballade. In developing these interpretations, the integration of Grieg´s subtle ways of eliding phrases, the constant feeling of opposing tendencies and interesting directional ambiguity in the phrasing are among the most important elements to the realisation of his style.

His Piano Sonata op. 7 is a lovely, energetic, and youthful piece of music, and in the collection of the nine Grieg recordings we find two of the movements (or rather one and a half). Performing the sonata has indeed its inherent challenges in the holding together of the piece, in avoiding an excessive sectionalising, something which is almost impossible to find a solution to in the score itself. There are several important performance elements that contribute in the process of creating an organic form, temporal modulation and ‘schwung’ being two (cf. ‘Tempo Modulation, Swing and Structure’). Grieg has also shown us how the multi-layeredness of his playing and ambiguous tendencies in certain areas are very effective as means of creating dynamic shapes and linking of otherwise simple phrase structures.

The kind of directional ambiguity we find in the above example and many other places has certainly influenced my own performance to a large degree. For example in the basic characterisation of the transitionary theme, before the entry of the development section in the first movement of the sonata:

…and as a blurring of the seem/join in the transition to the recapitulation in the finale of the Sonata:

http://www.chasingthebutterfly.no/wp/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Finale-

21.mp3

Ballade and ambiguity

Central to the dynamic realisation of the large scale variation work Ballade op. 24 is in our view the organizing of the many variations into larger groups or sections, creating an impression of larger basic structures with an overall coherence. In an ideal performance of the piece, the overall structure is even symphonic in its conception. In such a perspective, the interesting internal relation and finely tuned affinity between the variations and between the larger sections are of immense importance. A variation-by-variation approach with predictable transitions, where all tendencies/performance elements point in the same direction is very destructive to the realisation of this kind of overall, organic structure.

In this context, the reoccurring upbeat of the theme and the middle section of the theme as they appear throughout the piece are very important elements. In the first presentation of the theme it appears as a short and regular upbeat. I give the upbeat a little time, ‘swinging into’ the main beat, an approach to beginnings which is very typical of Grieg´s performances. This is a very characteristic and important feature found not only in the beginning of his performances but normally with the introduction of every new section. Sometimes it is barely noticeable, other times very clear, but it is always there. In my version of Ballade this treatment of the upbeat is creating a certain amount of metrical ambiguity in this first appearance of the theme, but less so in the return of the theme at the very end. The first appearance:

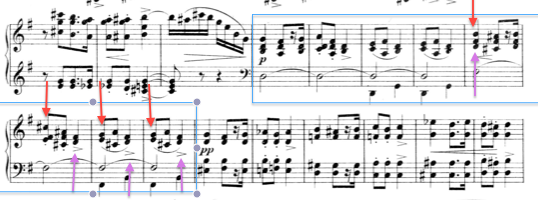

In later appearances, this upbeat and the upbeat of the middle section of the theme are transformed, now taking on more weight, and already in the second part of the 1st variation, the regular three part pattern of the theme is disturbed by a 2+2+2 pattern, and a 3 + 3 pattern in metric dislocation with the notated meter:

In the second variation, a strong 3 + 3 pattern (in fact 3 + 3 + 1 + 3 ) emerges inevitably, again contrary to the original metrical outline of the theme, and in metric dislocation with the notated meter:

As suggested above, we believe this ambiguity needs to be communicated – rather than ‘disambiguating’ or clarifying the statement. There has to be an interaction between the various metrical levels, and the inherent ambiguity needs no clarification, quite the contrary. The dynamic force of the directional ambiguity is the powerhouse here, it communicates the emotional essence of Ballade, and enables a sculptural approach to large scale form. This ambiguity can only be achieved through a sophisticated correlation of dynamic detailing and subtle tempo modification.

There are of course aspects to ambiguity other than the structural considerations mentioned above. In Grieg´s own playing, the ambiguity often communicates an emotional content essential to the thematic characterization, and perhaps even to the characterisation of a programmatic (extramusical) content. In To Spring, the opposing directional layers of the thematic material is creating the youthful urgency this lovely tribute to spring needs. And there is not a trace of the sentimentality this piece is so often indulged with. The directional ambiguity is definately an essential element of Grieg´s performance of the piece, and is indeed central to my concept of Ballade.

Another example is the Adagio, var. 3, where we would actually regard the metrical conflict appearing from the dislocated 3 + 3 pattern to be the very theme of the variation. This variation gradually burns out the energy of the previous variation, and appears as a kind of tail of it. The troubled waters gradually settle down, and the understanding of the dynamic power of the embedded metrical ambiguity we believe is the key to the effective realisation of this overall idea.

![]()

Clearly, there is no conclusive evidence in the discussion regarding ambiguity and multi-layeredness in performances. Identifiable multi-layeredness, or even the unidentifiable sense of an interaction between various simultaneous ideas and tendencies is still a mark of distinction in most forms of art. This internal ‘conversation’, usually within a clearly defined overall concept, is certainly an essential characteristic of the greatest music perfomances of this period, and in our view any period. In Grieg´s performances, there is a very suggestive multi-layeredness emerging from the innumerous ambiguous tendencies, it is indeed a very strong characteristic of his style.

![]()