Tempo Modulation, Swing, and Structure

Today´s mainstream performance style is in many ways the aftermath of an originally chosen delimitation with regards to performer- added tempo modification and gesture. This chosen delimitation appeared to a large extent as a counter-reaction to the excesses of the late romantic performance style. It is however a delimitation which is not chosen anymore. We are 21st century performers, and these delimitations have to a large degree become inherent in us. Our ‘spoken’ musical language is no longer the same, and we need to engage our will in trying to speak, or relearn this language. (cf. ‘Approaching a Performance Style’) We can´t easily return anymore to the sophisticated syntax of Grieg, and it is often difficult for us to grasp the greatness of Alfred Grünfeld´s or Paul Pabst´s musical narration. Our modern delimitations with regards to tempo modifications are in fact quite radical, when considering the performers of the early 20th century, and their way of dealing with this most important structural and expressive device. It was a performance element, which was probably taken for granted in any performance.

![]()

We know for a fact that performance styles have changed over the last century. This is not a subjective opinion. Based on a significant number of recordings, the research of the Mazurka Project at ‘CHARM’ (Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music) has documented a clear general tendency towards slower tempi, and less internal variation in tempi over the past hundred years. Synchronisation of the attack is another measurable performance element, which has changed radically since the early 20th century.

All these elements are quantifiable and often rather obvious performance characteristics. In our view, the most important in analysis is the identification of the less instantly recognisable and more finely tuned tempo modifications, and to recognise their effect on the performance. They are perhaps the main carrier of the musical narrative and the gestural content, indeed a source of life to this music. The finely tuned tempo modifications can break detrimental regularity. It allows for a sculptural approach to the phrasing, the multiple and overlapping directional tendencies, and consequently the full exploration of the line. It allows an autonomous development of the musical line – far less hindered by bar lines and paper structure than is customary today. There are an endless number of examples to support this. Listen to this touching performance by Carl Friedberg who studied with Brahms. He is playing Brahms´ Intermezzo in B flat op.74 no.4:

All these elements are quantifiable and often rather obvious performance characteristics. In our view, the most important in analysis is the identification of the less instantly recognisable and more finely tuned tempo modifications, and to recognise their effect on the performance. They are perhaps the main carrier of the musical narrative and the gestural content, indeed a source of life to this music. The finely tuned tempo modifications can break detrimental regularity. It allows for a sculptural approach to the phrasing, the multiple and overlapping directional tendencies, and consequently the full exploration of the line. It allows an autonomous development of the musical line – far less hindered by bar lines and paper structure than is customary today. There are an endless number of examples to support this. Listen to this touching performance by Carl Friedberg who studied with Brahms. He is playing Brahms´ Intermezzo in B flat op.74 no.4:

When hearing performers of the early recording era commonly considered modern in their time, such as Rachmaninoff or the somewhat earlier Busoni, many of us instantly recognise the very obvious differences in style in relation to more old-fashioned performers like Paderewski or Reinecke. When listening to these relatively modern performers, some might consider their style of playing rather common currency, a style not significantly different from what we hear today. After all, there are no mannered dis-synchronisations, their rubato is less abrupt and there are generally less radical tempo modifications. (In some ways this relates to Grieg as well, and we would probably neither categorise him as very old-fashioned nor among the most modern performers of his time.) There is some level of truth in this. On the other hand, we do believe this consideration all too easily takes the attention away from the quite extraordinary features of their style, representing anything but common currency today.

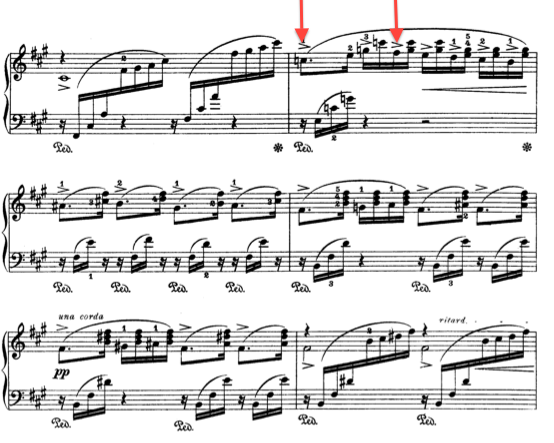

We often notice the finest tempo modifications, which prove crucial to the line and the phrasing. In the following example of Debussy´s Hommage à Rameau there are no dramatic tempo modifications, yet there is a spectacular phrase trajectory, a connection of the phrases, and a movable line, which is quite unlike the lovely detailed but rather localised Debussy we are all so familiar with. We are now moving into a repertoire not heavily represented in the early recording era, and it is indeed interesting to see how the first performers of this “cutting edge” repertoire dealt with finer tempo modifications. What we hear below is Debussy´s close friend Ricardo Vignes, indeed a modern performer of his time, to whom both Debussy and Ravel dedicated their music, and who premiered several of their most important compositions. Vignes is playing from Hommage à Rameau:

The fingerprint of a performance, that which separates the exceptional from the uninteresting, is often found on this micro level. We see the overall phrase structure being influenced fundamentally by small-scale tempo modifications. As discussed in ‘Ambiguity and Multi-layeredness’, the multiple and opposing tendencies in phrase junctions are also totally dependant on this. (cf. Rachmaninoff Prelude C-sharp minor). The relation between the two following examples gives a good indication of the power of micro-level tempo modification in connecting smaller phrases or blocks into larger dynamic entities. With regards to general tempo, it is very interesting to observe that these two examples are only separated by a couple of seconds in total duration!

The first example here is Paul Pabst, who was born shortly after the death of Chopin. He is by no means a source of Chopin performances claiming authenticity, but the first musician in history to record his music. Pabst was a Liszt student, born in Germany in 1854. He was a friend of Tchaikovsky, who described him as ‘a pianist blessed by God’, and was the unnamed virtuoso who helped the composer work his 1st piano concerto into shape. Here is the late Romantic tradition of pianism in full flight, the most sophisticated rubato, flexible but in fact highly structured. We hear fluid shapes that nevertheless have great strength:

Instead of the highly regular sectionalising of the phrase in the second example, Pabst gives the impression of flying low over a wavy landscape, and we never quite know where the bottom of the valley or the hilltops are. He is able to do this with a sophisticated combination of dynamic and temporal finesse, where the actual trajectory of the phrase never quite corresponds with what we expect to hear. There is indeed nothing wrong with the second example here, we don´t really miss anything until we hear Pabst.

ABOUT GENERAL TEMPO

Among many other elements, the overall or average tempo in musical performances has changed over the last century, and it has evidently changed towards using slower tempi. This is of course a very generalised observation of which there are many exceptions. Grieg himself was however on the brisk side even for his own time, and functions as a perfect example of this observation: “As a rule his tempi were faster than those usually heard in performances of Grieg works by other artists...” – Percy Grainger

Without any kind of empiric evidence, which the Mazurka Project at ‘CHARM’ provides – and as a highly subjective exercise – we will take a chance and give some indications of what we believe would be perceived as a ‘normal’ tempo with our 2011 ears for some of the pieces Grieg recorded. Without making any reservations, we would certainly claim that Grieg was playing his pieces considerably faster than what we usually hear today:

Reference:

Grieg:

Reference:

Grieg:

Reference:

Grieg:

When trying to establish a good tempo, the performer needs to consider a number of different parameters. Finding the basic character of the music is of course an overall consideration. In the faster pieces, we are often used to consider clarity as the foremost quality to preserve. “Don´t play it so fast that we can´t hear all the notes”, is a comment I believe most of us have heard a number of times. The demands on intelligibility are so often put on the small-scale detail rather than on the overall musical syntax. Focusing on articulation and technical details is of course good, but its detrimental effect on coherence in the gestures and the overall phrasing is far too often the price we have to pay.

Is there even a too fast to Grieg?

With Grieg, technical clarity is clearly not the decisive element in establishing a maximum speed. There is a great level of virtuosity in his performances, and Grieg never holds back. At certain extremes, the temperature of his performance and his pushing of the phrase does prevail at the cost of ‘clarity’. We of course don´t know quite what his playing would have been like in younger days, but his priorities are certainly clear enough. Our common primary concern regarding technical clarity, was not a primary concern of Grieg´s anyway. It certainly does not make him hold back. But there is of course a limit to everything, including tempo; and what rather seems to be Grieg´s decisive factor is keeping the ‘swing’. Even though his tempi sometimes are fierce, we never hear Grieg pushing the tempo to a level where he looses the ‘swing’.

TEMPO, ‘SWING’, AND ‘SCHWUNG’

The word swing is indeed a very woolly expression, a term which most people today don´t at all associate with classical music but use more exclusively with popular music and jazz. It is perhaps the most fundamental element upon which everything is built: It don´t mean a thing if it ain´t got that swing (Irving Mills/Duke Ellington).

There is however no reason why swing should be considered to be an exclusive domain of jazz and pop music. Quite the contrary, swing is one of the very basic elements of performances of most periods – certainly including Grieg and our other heroes from the early recording era. Swing is a fundamental element of Grieg´s piano playing, and a more integral part of his performances than with any recent recordings of his music that we have encountered. Grieg himself clearly considered swing, or what he calls ‘schwung’, to be an essential part of music making, and he mentions it several times in his correspondence.

But are we talking about the same kind of swing with the classical masters of early recordings as with Duke Ellington or for that sake Frank Sinatra? Yes and no is the simple answer to that.

What most people today would recognize as swing is usually found in music relating to dance in some way or another. If we rewind a century, (we would probably find the same if we could listen to music a century or two earlier as well) we actually find the same basic type of swing, created by the melodic centering on a recurring, regular, and often strong beat. This ‘centering on’ is precisely what creates the swing, and the performance of it distinguishes the master from the dilletante, and has done so all throughout history.

(Traditionally the melodic centering on a strict accompaniment is called Rubato – Italian for stolen time – and was mainly used for expressive purposes. By the time of the late Romantics however, the term Rubato had developed into something slightly different, evolving into a more generalised rhythmic flexibility – a momentary, or slightly more lasting ebb and flow of tempo. We find this kind of rubato in many of Grieg´s performances. Often, there is still the exact same feeling of centering on the beat, but now without that characteristic separation of the melody from a strict accompaniment. Even though we don´t find it in Grieg´s performances, there is still evidence of this other form of rubato manifesting itself as late as Grieg´s, not least in the performances of music by Chopin, who cherished this particular means of expression. At the time of Grieg´s recordings, it seemed to be gradually dying out. Strangely enough, it lives on in the 20th century in popular music and jazz, and it is hard to think of jazz and certain forms of pop music without it.)

There is a very characteristic, seemingly primitive quality to Grieg´s rhythmic impulses in the dance-based pieces. This is often created by an apparently unprepared and early placement of accents, usually centering on a strong basic pulse, which leans slightly forward. Against the backdrop of an extremely sophisticated playing style obviously routed in his German training, this is a very fascinating point. A ‘cultivated’ preparation of the accents (taking time before them), or simply neglecting the accents simply takes away Grieg´s loose and folk-like swing:

We hear exactly the same in Wedding Procession:

![]()

In the performances of Grieg and many other great performers there is however a different kind of swing in action as well, living alongside the dance-based swing. This is something rather different, and in our context, perhaps even more important. It is a type of swing that contributes to the shaping of single phrases and the linking of phrases – creating larger musical building blocks in a highly dynamic way. This dynamic or structural kind of swing has in fact an overall formal effect in Grieg´s performances, and we believe this is what Grieg had in mind when he talked about ‘schwung’. The Alla Menuetto from his Piano Sonata is a wonderful example of this:

This schwung permeates Grieg´s playing in pieces of widely different character. It is central to his his performance whether he is performing a dance-based piece like Alla Menuetto, or compositions like Butterfly, the finale from his Piano Sonata, or To Spring:

SCHWUNG AND STRUCTURE

Grieg´s particular kind of schwung plays a major role in giving an interesting structure or shape to his pieces, as it frequently works against the often very obvious paper structure we see on the page. His schwung is often non-regular and creates asymmetrical structures. In this way Grieg manages to build much larger and much more dynamic shapes, and there are never any dead points in his performances. Instead of emphasising the highly regular structure which appears so clearly on the page in for example To Spring, Grieg constantly passes over the obvious joins and ‘swings’ into other points of emphasis. There is an intricate interplay here between the musical ‘commas’ we expect to hear, and Grieg´s performed musical syntax:

When only considering Grieg´s written notation, the musical syntax in To Spring appears very simple and schematic – and the music suffers when the obvious ‘seams’ of the composition are further emphasised in the performance. Grieg avoids the very obvious 4+4 bar pattern (starting with bar 3) we hear in the following example:

Griegs´s way of interacting with his own notated musical syntax, his way of working against the obvious ‘seams’ of the structure, and his way of building much larger and dynamic shapes is one of the foremost features of his performance style. And it is simply impossible to arrive at this result from the notation alone. The impression of Grieg creating the ideas at the spur of the moment, the improvisatory feeling, is also delusive. In a piece like To Spring, we find exactly the same musical syntax when the thematic material is later presented in a different context and in a very different musical texture:

Grieg also confirms his consistancy in this when we compare the acoustic recording of Butterfly with his Welte Mignon piano roll recording from 1906, three years after the acoustic recordings. These recordings are less reliable and of far less significance than the acoustic ones, simply because they contain much less information. They are made from mechanical playback machines, and at this stage in time these are little more than advanced organ grinders. They are however important as secondary sources, and in the case of Butterfly, the piano roll confirms the structural ideas we are presented with three years earlier in the 1903 recording. The performed phrase here is not split into regular sections the way one would expect from studying the score alone, and it does not really adhere to the bar structure of the score.

Grieg 1903:

Grieg starts the phrase with an accent on the first note but deviates from the expected structural pattern immediately after. The C# indicated in the score is in theory given a minimum of weight from its position in the bar. It does however have a dissonant Tritone relation to the accentuated G natural at the first beat of the bar, which Grieg emphasises in his performance. He attaches the line to this C#, and takes a dive. The descending line ends only when he hooks up for another dive at the very early placed C natural marked in the score and its corresponding F#. The way Grieg hooks onto the next line by slightly anticipating the C natural makes the musical lines overlap each other in a very sophisticated way. There is a tantalising feeling of physical imbalance and a re-establishing of that balance later, and in other places than what one would expect. In the Welte Mignon we don´t hear any convincing dynamic accents because of the limitations in the technology, but we hear the agogic effect of them.

Welte Mignon, 1906:

If we side track to an example from another article on this web, ‘Ambiguity and Multi-layeredness’, we find Rachmaninoff performing his own Prelude Op.3, no.2. This is another example of a clear structure in the performed phrase, which is simply not traceable in the score. Again we see a performance which deliberately disguises the ‘seams’ of the written structure, or rather interacts with it in a highly sophisticated way. Rachmaninoff recorded this piece many times, and although his version differs slightly from each other, there are basic elements of his performed phrase structure that are exactly the same. And his way of shaping this material has very much in common with Grieg´s way of shaping To Spring:

The example above is recorded in 1928. Rachmaninoff also recorded this piece almost ten years earlier, with Edison in 1919. Listen to the remarkeable correlation between these two recordings with regards to the phrase structure. There is a total consistency in his structural ideas:

|

Rachmaninoff complained about the recording sessions with Edison, who apparently made him record on an upright piano. The photo shows a similar Edison recording session.

|

![]()

Grieg, the composer, is generally criticised for his schematic structure and the lack of development within the music. The seams of the structure are very apparent on the page and often reinforced in performance. However, when listening to Grieg playing, we often get the impression of a very improvisatory and flexible character, as if the shape and the length of the musical units are being decided on as the pieces progress. What our studies have shown us, though, is rigid structural patterns on which a given phrase is moulded – where Grieg performs the same melodic material in a surprisingly fixed, however extremely sophisticated way, even in very different textural contexts. This is not to say that it sounds stiff or academic in any way, far from it. He creates a dynamic structure, a framework that enables him to form the smaller elements with the freshness of the newly made. In his own performance, Grieg actually counters his critics by constantly moulding the audible structures counter to the square visual structures of the score. His performance of these short pieces are actually so rich in content that they take on far larger structural significance. One could describe it as being macro structures on a micro level. The level of detail however, never undermines or disturbs the overall line. Quite the contrary, the details of the performance all seem to cohere closely with and support the overall structure.

Working over such a long time with these recordings, it actually strikes us both how much of a strong inner logic there is to every detail of these performances, what consistency there is to every rubato, every bit of articulation and to every transition. We have earlier been spending a very considerable number of hours studying other great performers and can assure that this impression of total consistency is not only formed by spending enough hours listening to these performances.

![]()

‘NON-TOGETHERNESS’

‘Non-togetherness’ or non-synchronised attack is a very characteristic and important element of older performance styles. With many performers this was a very natural and highly effective way of giving the phrase a feeling of schwung. The synchronisation of attack is a performance element which seperates the more modern performers of Grieg´s time from the old school performers. Very important though – even with the most radical performers of the time, we don´t find piano playing clinically devoid of non-synchronised attacks, which is more of a modern ideal. With many modern pianists of this period we find the spread attack used for local, structural purposes – it is to a greater degree marked in their style.

With Grieg, the non-synchronised attack is a less prominent feature. The highly prominent and regular non-togetherness is a feature of the more old fashioned performers of this period, such as Reinecke or Paderewsky.

When studying this particular performance feature, it is of great importance to avoid the piano rolls. Anyone would rightly shake his head when listening to something like this:

The problem is that a pianist like Reinecke and many other old school pianist recorded on piano rolls only. On a primitive piano roll system the non-togetherness is simply shocking, and becomes the only noticeable feature. None of the other performance elements seems to attract our attention.

Only when listening to the subtle elegance and finesse of the following example we realise what extraordinary qualities can be found in this style of playing. Regardless of any stylistic considerations: nothing but an acoustic recording will give a fair representation of the delicate non-togetherness we hear in the following example by Paderewski:

Grieg is thus a relatively modern performer. However, there is even in Grieg´s playing a certain amount of non-togetherness, and he uses it consistently and very subtly to create swing in Remebrances. Notice particularly the way in which he introduces this effect on the less weighted second and third beats of the bar, and the way in which the non-togetherness gives an upward direction, which clearly contributes to the swing:

SCHWUNG AND ‘MUSICAL GRAVITY’

In the example above we hear how the anticipation of the beat – sometimes the second, sometimes the third – creates Grieg´s characteristic ‘upward’ swing. Feeling the after-beat, or what is happening between the weighted beats, is indeed the most important part of creating swing or schwung. There is an interaction between the expected and the performed beat, and I believe this has to do with our sense of ‘musical gravity’.

A sound is not pulled to the ground like an object, but the life span of a piano tone has very much in common with the trajectory of a ball being thrown into the air. It feels like it is being affected by forces of gravity. This trajectory fundamentally affects the way we perceive a musical gesture or feel the natural span of a phrase. It creates an expected line, with which the masters are capable of interacting, the way passing winds give new lift and constantly change the curve of a glider on its way to the ground. Listen to Benno Moiseiwitsch in the following small section from Schumann´s Symphonic Etudes:

Grieg´s greatest example of this interaction with ‘gravity’ is the Alla Menuetto, where he sometimes slightly anticipates the third beat with great energy and gives renewed force to the melodic curve. Grieg´s schwung can also be described as opposing tendencies in the performance, and particularly from opposing tendencies of flux or resistance. The highly sophisticated interaction between momentary holding back and letting go is an important key to Grieg´s great schwung in the opening of Alla Menuetto.

A similar kind of correlation between the main beat and after-beat in the ‘funeral variation’, slightly affecting the expected trajectory, proved to be the key to solving this difficult section of Ballade (cf. ‘Prelude and Trouble at Troldhaugen’).

We have shown some examples of how Grieg molds a phrase around on the less weighted beats, which is central to Grieg and central to so many performers of his time. With Grieg this appears most clearly in the pieces that are not dance-based. If we listen carefully, we will however hear that Grieg, even in the apparently regular and rhythmicly firm dance pieces, pays particular attention to the less weighted beats. This is another element, which seperates him from almost all other performers of his own music. Listen to the following section of Wedding Day at Troldhaugen:

![]()

If we are to conclude with regards to general tempo: what we see from studying Grieg and a number of other performers is that a high general tempo, in combination with a strongly present schwung or structural swing, usually helps clarify the musical superstructure. This consequent emergence of the higher degree lines, or musical superstructure, is strikingly evident in all of Griegs´s performances.

When did the overall line of To Spring ever appear as strongly as in Grieg´s own performance?:

And listen to the effect of the extraordinary tempo in the finale of the Piano Sonata:

The realisation of a clearly defined musical superstructure, strongly present as in Grieg´s own performances, has been a clear ambition in our work on the Piano Sonata and Ballade. Keeping the schwung and the interpretative detail within extreme tempi is a formidable challenge, and I consider tempo an absolute necessity for the proper realisation of an overall, symphonic structure as in the crucial last third of Ballade. Here, and in several other places where the most rapid tempi are nessecary, I have still tried to let the constant presence of scwhung be the decisive element where a maximum tempo is required:

In a similar way to Grieg, I have tried to implement his schwung and way of molding the phrases in all my performances. It should be a fundamental element of both the slow movement in his Piano Sonata, and of the various variations in Ballade:

Unravelling the many secrets behind Grieg’s peculiar form of swing or schwung has been a particularly rewarding exercise, using this method of recreation. There is hardly any element in performance that suffers more from verbal explanation or notation than swing, and yet this is of utmost importance in Grieg’s own style of performance.

![]()

TEMPO MODULATION

The word modulation is a term we commonly associate with the harmonic transfer from one relatively stable tonality to another. As we know, this is a part of the composer´s domain and not subject to the will of the performer. The word can however be used in relation to tempo as well – tempo modulation – meaning the temporal transfer from one relatively stable area to another, a transfer which goes beyond the normal, unmarked flexibility.

When studying performers, and particularly when observing composers performing their own music, the interesting part is the performed tempo modulations, which are not indicated in the score.

On a harmonic level, the modulations themselves – the manner in which the composer moves from one key to another – can often be of great interest. In a similar way, the actual transfer from one temporal region to another can itself be worth investigating. The opening of the Alla Menuetto is such a place. Grieg begins the movement at almost half speed, which is not indicated in the score, and moves to full tempo within relatively few bars. Grieg achieves this with a highly sophisticated interaction between the hands, and with opposing directional tendencies in the material. He holds back and lets go, with a strong and constant underlying forward motion:

In other places we are not talking about a modulation ‘per se’, but more of a sudden lift or pull to a new temporal region, or what we can call a metamorphosis.

![]()

Local tempo modification, or rubato, is something our notational system doesn´t really come to grips with. One would on the other hand consider larger-scale modulations something of an easier thing to indicate within our established notational system. In ‘Musik-Lexicon’ (1882) Hugo Riemann comments on the subject of tempo changes: “…for whole movements, they are of such extent as to be seldom ignored in the notation.”

On this basis it is particularly interesting to observe how Grieg introduces a whole number of large-scale tempo modulations, which are not indicated in his own score. Large-scale in this context are the modulations that are operating within a time frame of 3 minutes or so (which was the average limit of the recording medium at the time), but still affecting major sections within the pieces.

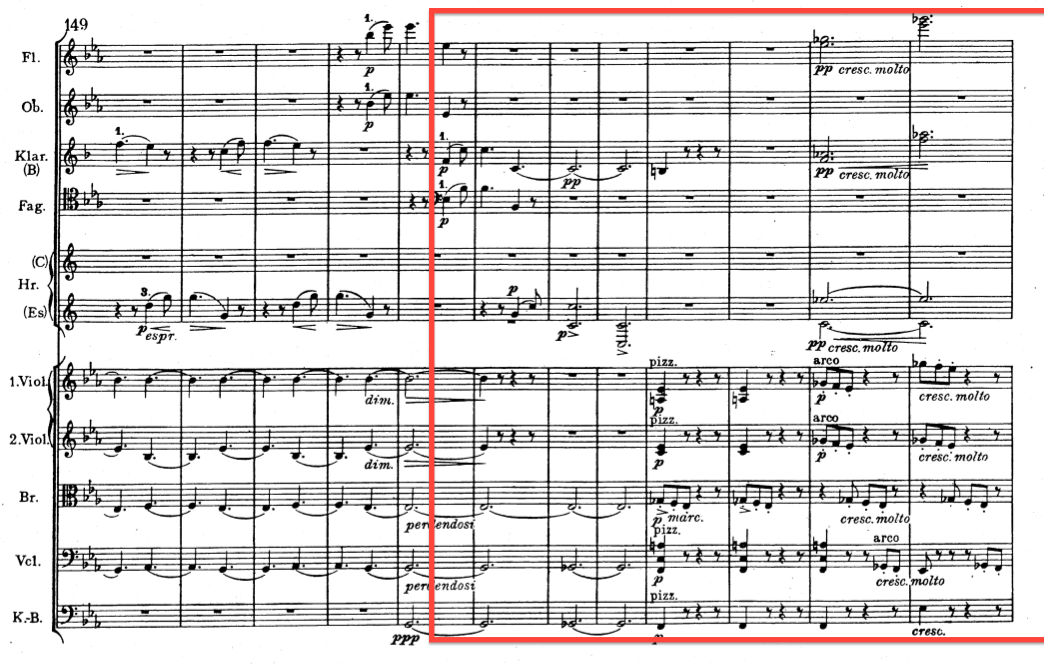

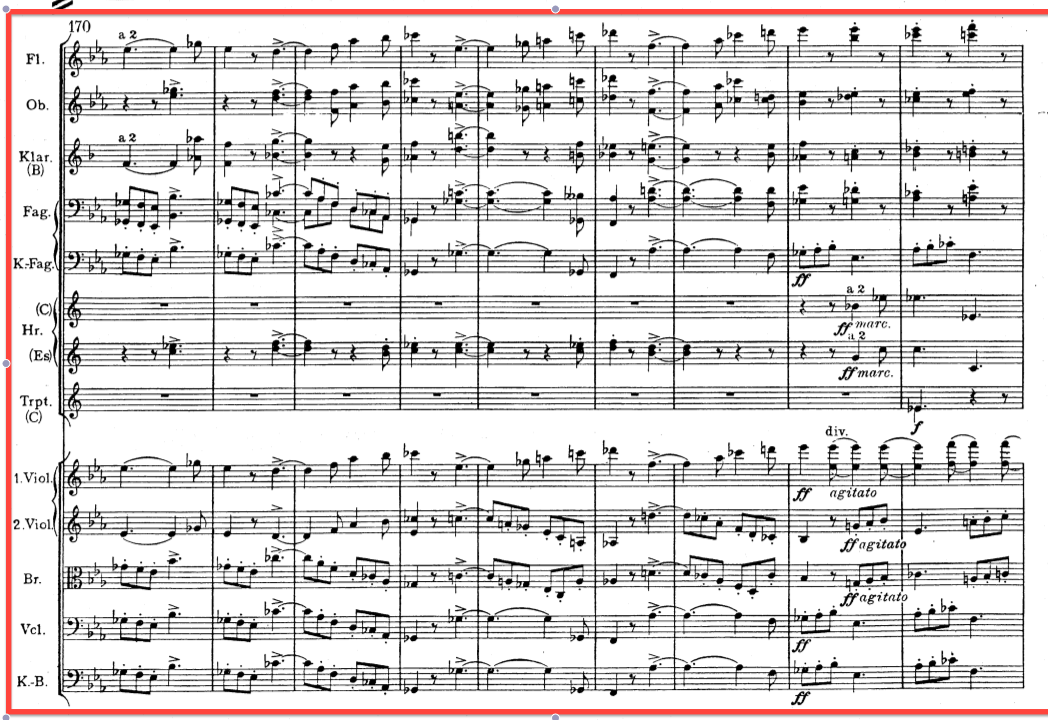

There are of course numerous examples of performer-added large-scale tempo modulation in recorded performances, one notable example being Willem Mengelberg/Concertgebouw´s recording of Brahms 1st Symphony, 1st movement, indeed a benchmark performance of this symphony. Mengelberg was highly influenced by Mahler, who followed the line from Wagner regarding flexibility. The tempo modulations here are very pronounced, and I consider them the strongest single element in defining the overall architecture of the movement.

Listen to the marked section in 1. Mvt, where there is a slow 2 (6/8) beat, even with a slight feeling of the underlying quaver.

From this region there is a modulation, where Mengelberg emphasises Brahms´ cross-rhythm. The feeling of three beat to the bar gives incredible momentum to Mengelbergs modulation…

… to more than double speed and a clear sense of one-beat to the bar and an exceptionally long line in 12 after E.

If we steal from the terminology of physics, the following ‘carved in stone’ climax is given its extraordinary ‘potential energy’ from holding back the tempo considerably, like a dam holding back a massive pool of water, retaining all of it´s potential energy for a (partial) release where a new stabile temporal region is introduced at the end of the example.

In both cases (Grieg and Mengelberg) these are all temporal modulations that do not have an indication in the score. But in the case of Mengelberg, he is not the composer. Grieg is.

There is no question that many other conductors of Mengelberg´s generation performed this symphony with considerably less pronounced temporal modulations. However, one would need to search hard to find any pre-war recording, or indeed any older recording of the piece that makes absolutely no attempts of shaping through tempo modification. In the latest recording with Berliner Philharmoniker their chief conductor Simon Rattle ignores this aspect completely. The following is a random edit between various parts of the same Brahms movement:

This represents an aesthetic where an immovable pulse is made into a virtue, a rather alien approach to most performers in the early 20th century. The sound of the orchestra is luxurious, the musicians are fantastic, but the treatment of tempo is very static compared to Mengelberg.

Felix Weingartner was a conductor who revolted against the tradition of flexible tempi, but his conducting was admired by Brahms himself. At least the performances of the young Weingartner was admired by the old Brahms. We have to acknowledge the fact that these questions were subject to controversy even in this period, and there were opposing views. For this reason it also interesting to look at this other extreme from Mengelberg and Mahler – the representatives of a more straightforward approach to tempo such as Weingartner and Toscanini. Comparing Rattle and Weingartner, there is still no question that Weingartner displays a significantly greater level of flexibility than the Rattle example above.

This is evident not least with regards to a very specific type of modification, the rushing towards a high point or climax of the musical sentence or section. The recorded evidence of Brahms himself from 1889 is very limited in quantity and quality, but his tendency of rushing towards the high point of the musical sentence is very characteristic, particularly in the second part of this Hungarian Dance:

It is highly important to include performers from the so called HIP-movement (Historically Informed Performance) or the Early Music Movement in this discussion, and most specifically with regards to large-scale tempo modification. There is a wide range of individual musicians, groups and orchestras exploring this terrain with fascinating results. Listen here to Nikolaus Harnoncourt conducting the finale of the same Brahms symphony with the same orchestra as above, the Berliner Philharmoniker.

![]()

Returning to Grieg: even though we cannot draw the conclusion that we are free to introduce temporal modulation at liberty, we believe that his consistency in this respect – the fact that he introduces significant temporal modulations outside of his own indications in more than half of his recordings – makes it reasonably safe to assume that this was a common practise for Grieg. It was something of a performer´s privilege, and we believe Grieg would probably treat a composition by others than himself, certainly by his contemporaries, with the same liberty in tempo.

HOW DOES THIS AFFECT MY PERFORMANCE?

Categorising tempo modulation in a context of great flexibility can of course be a difficult exercise. Sometimes it appears very clearly to the listener, other times it is barely noticeable, and seems only like a subtle change of spirit.

Giving the phrase a forward direction with a consequent lingering is a romantic performance strategy, which to some level has become an integral part of my own performance style. The structural swing mentioned above will also have a disturbing, local effect on the basic pulse. What distinguishes the tempo modulation though is the transfer to a somewhat lasting and relatively stable level of tempo. The absolute and mathematical relations here are uninteresting to most of us, so in the following I will direct the the listener´s attention towards some of Grieg´s, and my own intended tempo modulations. I would of course hope they are perceivable to the listener at some level as well. Most importantly, I hope the effect of the modulations comes across, which is far more important than recognising any mathematical relations.

Grieg usually introduces his non-indicated tempo modulations at strategically important places in his compositions, often in order to distinguish individual themes. He lifts the tempo quite considerably when moving into the 2nd subject of Bridal Prosession, and does exactly the same when moving into the 2nd subject of the Humoreske:

Interestingly enough, Grieg does not use temporal modulation when moving into the 2nd subject of the finale in the Piano Sonata – and even though he modulates in the Alla Menuetto, he does not modulate between the 1st and the 2nd subject, and makes a ritardando but does not modulate when moving into the Trio section:

Thus, Grieg is not completely consistent in this respect, but we do a hint of how and where he introduces these modulations.

![]()

Much in the manner of Grieg´s performance of the sonata movements, I find it appropriate to introduce tempo modulation in the two remaining movements as well. I move between various relatively stable temporal areas, which define structurally important areas of the piece.

In the 1st movement of the Piano Sonata my chosen areas of tempo modulation are in entering the development section, the entering of the recapitulation, and at the very end of the Coda.

In this movement I have also chosen the same strategy used by Grieg in the 3rd and 4th movement, and keep the same basic tempo when entering the 2nd subject.

The development section of the first movement is of a rather schematic and repetitive nature. Perhaps in lack of a thorough compositional development, the concept of development can be strengthened in the actual performance by illuminating the various temporal facets. Eliding the individual parts of the following sequence, and constantly changing the focal point of the motive is one solution:

Moving back to the introduction to, and the beginning of the development section: this appearance of the main theme can easily seem banal and needs space and ‘schwung’ to acquire the implicit heroic character. A certain amount of non-togetherness in the attack is intended here. In the score, Grieg himself indicates a ritardando, a gradual slowing down of the tempo, towards the beginning of the development section. However, rather than returning to a very definite tempo 1 at this version of the main theme, I deliberately modulate into a slightly broader tempo, which then prepares the temporal development that follows:

In the development section, I consider the tempo modulation itself – the actual travelling from one tempo to the other – to be of great importance. In the modulation from the temporal region of the opening of the development section to the recapitulation, there is an important balance between holding back and letting go, between levels of resistance or flux, which I consider to be a developmental subject itself. My version of this section is to some extent modelled on the opening of Grieg´s Alla Menuetto, where the slight metric displacement of the third beat octave in the left hand ‘swings’ the tempo up with a feeling of a circular movement.

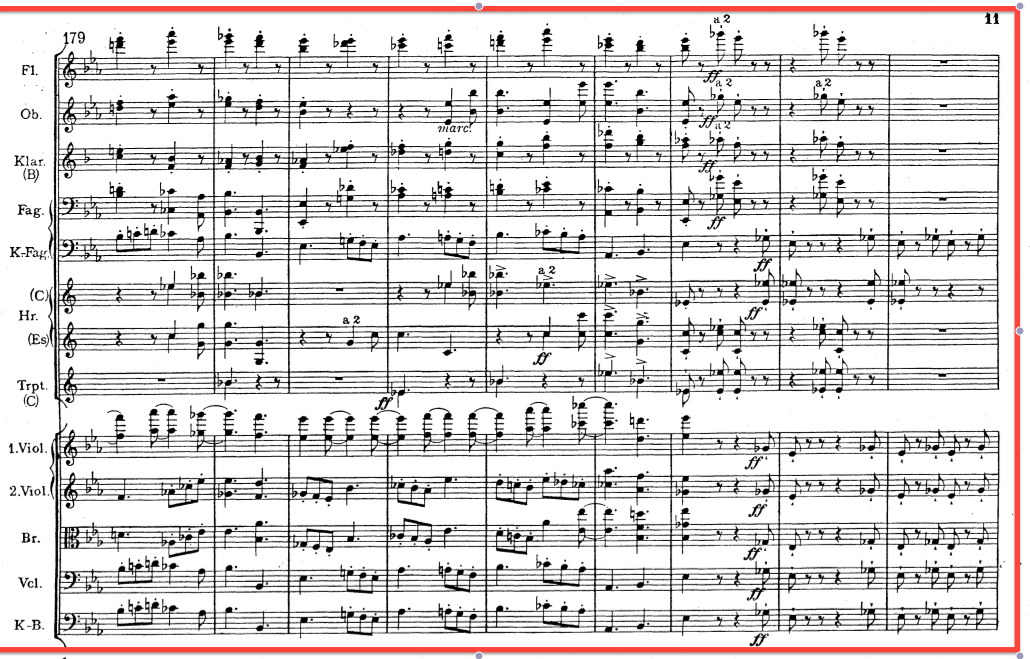

In the central sequence of the development section, there is a modulation with an overall forward direction from bar 2 in the score below. This points towards a new and relatively stable temporal region at bar 26. I then modulate the tempo almost linearly down from bar 34 to a completely new temporal region at the recapitulation, before returning to Tempo 1 at bar 48, 11 bars after the actual point of recapitulation. The structure of this return to the recapitulation is modeled on Grieg´s transition to the recapitulation in Butterfly.

LINEAR MODULATION

Grieg and many of his contemporary performers occasionally introduce this linear modulation of tempo. It appears at certain structurally important places in a composition.

Generally speaking, it is hard to find any transition or tempo modulation in Grieg´s performances – as with many other performers of the time – where all tendencies point in the same direction. When it actually happens, it gives a striking effect. This linear change of tempo in a context of total flexibility is a very powerful tool in articulating musical form. Grieg´s normal way of modulating from one temporal region to another is to ‘swing’ his way into the new tempo, which is exactly what he does in the beginning of Alla Menuetto, or as a sudden lift to a new region, which he does for example in Wedding Procession.

The following two examples do however modulate differently but to great effect. In a context of flexibility and great freedom in the phrasing, we suddenly hear an almost mechanically measured modulation into a new section. This gives a striking emphasis on the new (or the repeated) material. The effect in this case is a feeling of release, moving into the new section – a release of the strong tension created by the preceding rigid modulation. (This example is also referred to in ‘Ambiguity and Multi-layeredness’, where the unclear directional character of the same few bars are discussed):

Here is Percy Grainger performing Chopin Piano Sonata B minor, the transition into the second theme of the 1st movement. We hear the same strategy as Grieg´s in Butterfly. The tension created by the linear modulation and the consequent release is however even more striking:

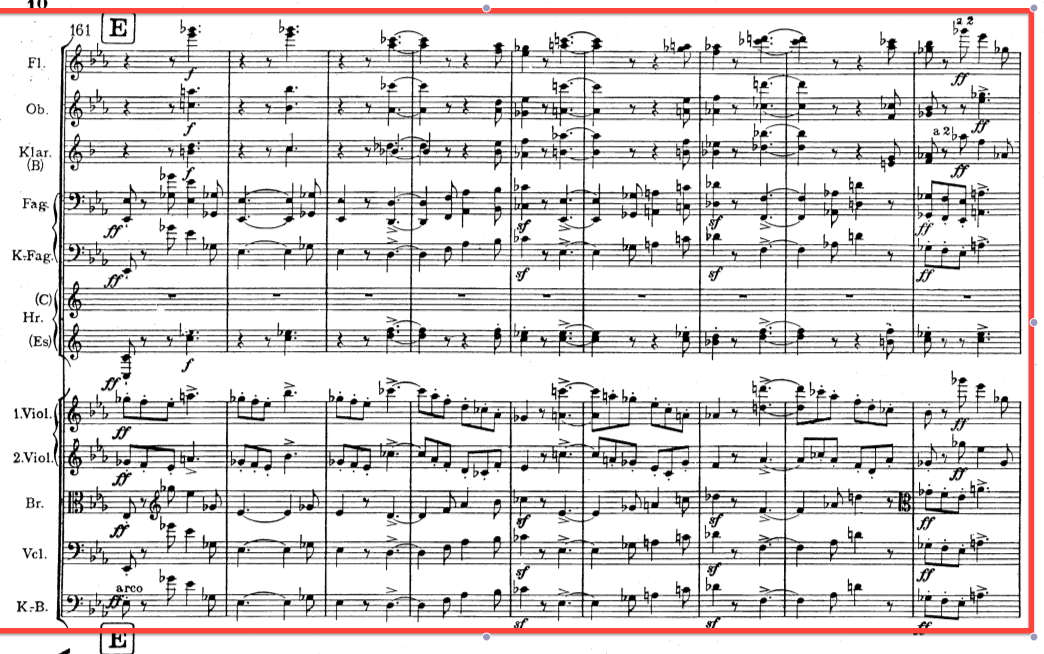

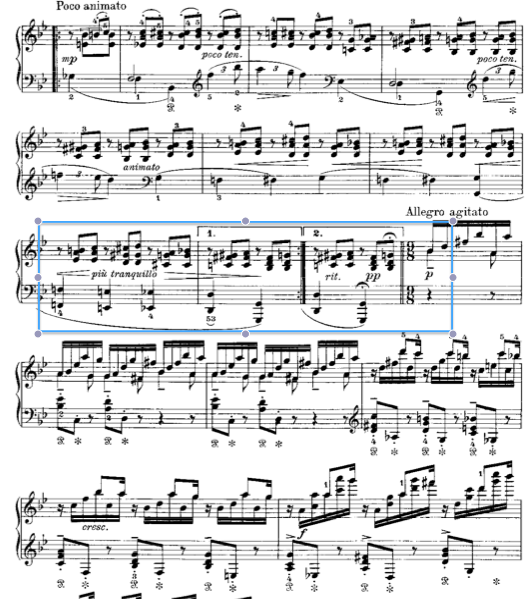

Though perhaps a little less rigid in the execution, there is in my performance of the following example from Ballade also an intended linear modulation. Again in a context of flexibility, I now move into the important first energetic variation of Ballade. There is a ritardando indicated by Grieg in the score, but in my view, the linear modulation works as a functional/structural pointer only when emerging from a preceding flexible environment:

![]()